A Brief History of The Universal Microscope

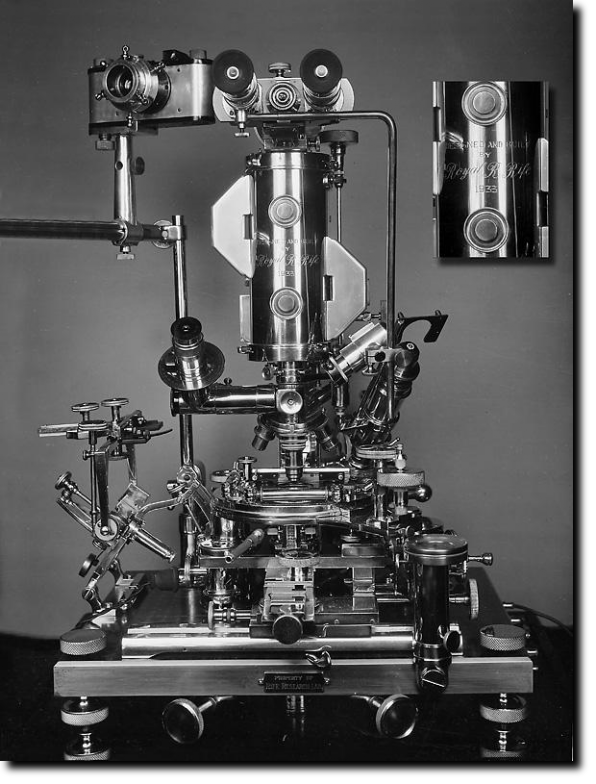

Royal Raymond Rife was the inventor of the Universal Microscope which he presented to the world in 1933. Besides being the most powerful optical microscope ever made up to that time, it was also the most versatile. The Universal used all types of illumination: polarised, monochromatic or white light, dark field, slit ultra and infra-red. It could be used for all manner of microscopical work, including petrological work or for crystallography and photomicrography. According to a report submitted to the Journal of the Franklin Institute it had a magnification of 60,000x, and a resolution of 31,000x. The ocular of this instrument was binocular, but it also had a detachable segment lower in the body for monocular observation at 1800x (x=power) magnification.

One of the most attractive features of this microscope is that, in contrast to the Electron Microscope, the Universal Microscope does not kill the specimens under observation and affords observation of natural living specimens in all circumstances, meaning it does not rely on fixing or staining to render visibility or definition.

Rife achieved this by using various modes of lighting to bring virus into visibility in their natural colors. He first turned to this technique of using light to stain the subjects because he realised that the molecules of the chemical stains were much too large to enter into the structures he sought to visualise. Furthermore, the typical stains used in microscopy are sometimes lethal to the specimens and he wished to see them in their live state.

One factor enabling these natural images was Rife's use of a device called a Risley counter-rotating prism. This consists of two circular, wedge shaped prisms, mounted face to face and set in a geared-bezel, and so geared as to turn each prism through 360 degrees in opposite directions by means of an extended handle. Rife built a special mount under the stage to accommodate these instruments, and through which he directed a powerful monochromatic beam from his patented lamp. At various declinations of the refracted and polarised ray normally invisible bodies would become visible in a color peculiar to their structure or chemical make-up.

All optical elements in this microscope were made of block quartz, which permits the passage of ultraviolet rays.

Rife began research work on tuberculosis circa 1920. In a short time, it became apparent to Rife there was something else involved in this disease below the level of the bacterium. This spurred his work in developing his "virus" microscopes, of which two preceded the Universal, which is sometimes called the number 3 Rife microscope. Rife was the first worker known to have isolated and photographed the tuberculosis virus, as well as many others. Eventually, Rife also succeeded in isolating a virus specific to cancer, finding it gave off a distinctive purple-red emanation. This virus he named the BX virus: Bacillus X, found in every instance of carcinoma he examined.

With the assistance of Dr. Arthur I. Kendall, using a special medium Kendall had developed for culturing virus, they succeeded in culturing the BX virus. They had little success at first until Rife accidentally left a tube in the glow of an ionizing lamp. He noticed the tube had clouded, indicating activity. Then they performed the culture in a partial vacuum, or anaerobic environment and stimulated them with the ionizing light. Their work was the first successful culturing of virus outside a living host.

Rife extracted the cancer virus from an "unulcerated, human breast mass". He filtered, cultured and recultured these over 10 times over a two hundred and forty hour period. They injected the last generation culture into the breast region of a live rat. The rat would inevitably develop a tumour. Rife would then remove the tumour, extract the virus, and repeat the process. He did this over four hundred times removed from the original sample, proving categorically that the BX virus induced cancerous tumours in every instance.